by Peter Condyles November 2021

Landmarks help define place. Many cities across the United States, and across the world would be indistinguishable without certain landmarks that have become synonymous with them. What would Paris be without the Eiffel Tower? Could one pick out St. Louis from another midwestern city without the Gateway Arch? Would the Seattle Skyline be different from that of any other waterfront city without the Space Needle dominating the landscape? As humans, across many cultures, emphasis has been put on landmarks that create a sense of community, and in many places a sense of belonging. While some of the most recognizable landmarks across the globe come from big metropolitan cities, the fact of the matter is landmarks are present and important in the smallest towns, as much as they are to the biggest cities. Right here in Washington small towns celebrate and revere landmarks that make them unique, and separate them from just another small town. In Winlock one can visit the world’s largest egg, and Mount Vernon has their smoke stack, now painted to celebrate the vast Tulips Fields of the Skagit Valley. A little farther north, the city of Blaine celebrates its proximity to the Canadian border with the Peace Arch. In Marysville, its community landmark has been intertwined into the life of that town for one hundred years now, and that is the Marysville water tower. While not on the same level as the Eiffel Tower, citizens of Marysville are equally as attached to their community landmark.

A Tower Born of Controversy

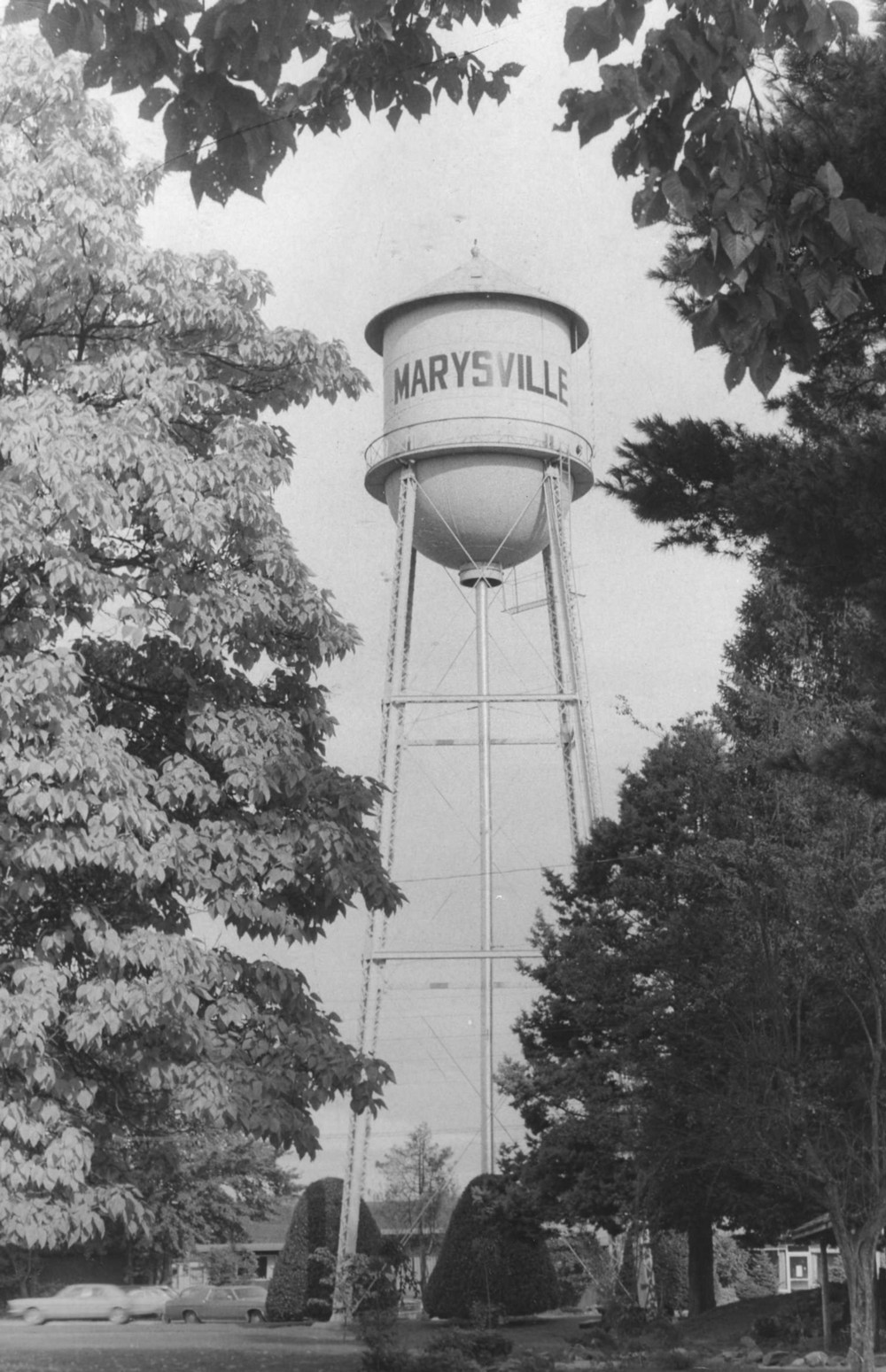

Marysville’s water tower has watched over the town as it grew from a sleepy hamlet on Highway 99 to the second largest city in Snohomish County. The water tower has been one of the only constants in the city for the past century, and on November 17th, 2021 Marysville will celebrate the landmark’s one hundredth birthday. The water tower has grown and adapted with Marysville, changing its purpose and its use to fit with the needs of the city. Originally built as a storage tank for the city’s water supply, its construction was desperately needed, and allowed the city to continue its growth by having clean reliable water. As the city grew and city services became more complicated the tower shifted its service to help the Marysville Police and Fire Departments more effectively do their jobs. In recent years the water tower has become a community gathering place, and a way for the city to celebrate, especially around Christmas time. The history of Marysville’s landmark however is not as cut and dry and it would seem. Its construction was an issue that nearly divided the town and saw immense political consequences, and in the decades following, its position as a community asset was not always a given, even up to the present. Nonetheless, Marysville’s water tower still watches over its city, one

As Marysville began to return to normal life after the end of World War I in 1918, the realities of the antiquated and overburdened city water system had become all too apparent. People were moving to Marysville, and the water system could not keep up. For many years the city had purchased water from the Rucker Brothers, who operated a system that pulled water west into Marysville from Lake Stevens. With the growth of businesses, industry, and residents, the system from the Rucker Brothers did not have the ability to grow the way the city needed. Throughout 1919 and 1920 city leaders explored different systems they could construct in Marysville, as well as different sources of water. Optimism regarding a new water system rose and fell during this time, and many options were explored. To better inform their decision, city leaders hired R.E. Koon of Portland to be the Water Superintendent earlier that year. During the meeting at the opera house that autumn evening of 1920, Mayor Hilton and Koon presented the citizens with the four options they deemed to be the best solutions to the water problems in Marysville.

- An expanded water district from Fobes School to Marysville, with water coming from the Skykomish River in Sultan.

- A Marysville water district, receiving water from Edwards Springs north of Lakewood.

- A Marysville water district, receiving water from Kickam Springs near Ross Lake on the Tulalip Reservation.

- Digging a series of wells throughout the town to service residents in certain areas.

The first option had been explored earlier in 1920 with little interest from Marysville residents, only 91 signed a petition to create the large water district. The fourth option was more of an emergency last resort, should the other three not work out. This left water sources at Klickam Springs, and Edwards Springs. At the meeting, majority of Marysville residents agreed to support a bond measure on the November ballot that would generate $84,000 to construct the new system. A few weeks later at the October 4th Marysville City Council meeting, with a full audience, the city council voted to purchase Edwards Springs from A.C. Edwards, and place two bond measures on the ballot the following month. While there was much community dialogue regarding which was the better option, the bond measures ultimately passed with 72% of the vote. With that hurdle taken care of, city leaders began the work of drawing offical boundaries for a water district, and finalizing the sale of Edwards Springs. While all this was taking place, the city was also gearing up for the regularly scheduled December city council elections, and for the second time in two months, the water question was on the ballot.

Three city council races were on the December ballot, with two members running for re-election running on the “Progressive Ticket” and the challengers running on the “Citizens Tickets.” While these might have been the official names, many in Marysville began calling the Progressives the “wets” referring to their support of the current water plan, and the citizens ticket as the “drys” referring to their opposition to the water plan. The drys, that to this point had been very quiet, believed that the water district boundaries were too small, and placed too high of a financial burden on Marysville residents when it comes to paying for the new system. Thomas Reed, a vocal member of this faction published many editorials in The Marysville Globe showing how high the connection prices would be for those wanting to hook up to the new city water system. In addition to this, Drys did not believe Edwards Springs had proved itself to be the best option, and thought city leaders wrote off Klickam Springs too quickly. For two weeks at the end of November 1920 the water issue was relitigated in the court of public opinion, with those who were supportive of the plan earlier that month, questioning their vote on the bond measure. On Tuesday December 7th, Marysville residents went to the polls and back tracked on what they had said just a month earlier, sweeping “dry” candidates into all three city council positions.

The following week at the final city council meeting of the year, a delegation of citizens who identified as “dry” filled the city council chambers. This was an exercise in futility, as the first order of business was to postpone any decisions on the new water system until the new city council is seated in January. Outgoing members believed the election was a direct repudiation of the water plans, and that the citizens did not want to move forward with them. The drys had won the election, and now they must govern.

The Drys Take Over

The new city council, with a “dry” majority met for the first time in early January 1921. At this meeting a petition was presented from the “wets” requesting the city continue to move forward with the plans as written. Newly seated councilmember W.H. Roberts then took the floor and explained that he was not in fact a “dry” and that he had always been a “wet” but those who opposed the water system supported him during the election simply because they did not want to vote for the incumbent members. After much discussion that evening, it was decided that a larger water district was the preferred path forward as to appease the drys, while proceeding with the plans to purchase Edwards Springs as to appease the wets. Over the next month city leaders met with citizens from both factions to work out the details, and on February 7th a new enlarged water district was passed. In addition to this, all previous work done on the water system was voided, including the election from November 1920 approving water bonds. City leaders then set a date for a new water bond election, which passed with 65% of the vote three months later in May of 1921.

With the entire community once again behind the water plan, and the bonds once again passed, the city council finalized the purchase of Edward Springs on June 20th, 1921 for $5,100. It was at this meeting that the first discussion of a water tower took place, when engineers described the need for a 240–245 foot tower to be 30,000–50,000 gallons. The city council officially opened the project to bids in late June, and a month later after reviewing the four bids received, awarded the contract to H.W. Troutman & Co. of Seattle for a sum of $73,655 ($1,128,700 today) to begin immediately. This included the construction of waterpipes from the springs, into the city, as well as the construction of a water tower in Comeford Park on land the city already owned. The next week 65 men began the long and back breaking process of digging ditched from Edwards Spring north of Lakewood into Marysville.

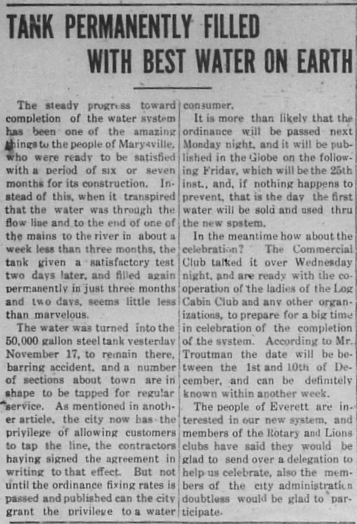

On September 22nd, the ditch diggers reached the site of the future water tower officially completing the process necessary to bring the wooden water pipes into Marysville. It was that same day that the concrete base for the water tower was poured. In The Globe that week it was said that the “city resembled a French battlefield” with trenches being dug along every street to bring water connections to the various neighborhoods. A week later on October 7th, The Globe reported that the 50,000 gallon tank for the water tower had been shipped from the Chicago Bridge & Iron yard in Chicago Illinois. The engineers for the project speculated that the tank would take about 2–3 weeks to arrive in Marysville, and there was a possibility that water would be flowing through the city system by the middle of November. This prediction would end up being spot on, as on November 17th, 1921 the first Marysville water tower will filled with water for the first time and took its place as a dominating figure in the Marysville skyline. The following day The Globe celebrated the occasion running the headline “Tank permanently filled with best water on Earth.” Even to this day it is one of the tallest structures in town, so imagine what the tower must have been like in 1921 when the tallest building in down was the Marysville Bakery building on 3rd (now the Dutch Bakery). For the time being, the Marysville water tower was an integral component to the city’s water works system, but as the years went on and the city grew it would take on a new roll, one meant to keep citizens safe.

Keeping Marysville Safe

For nearly the first century of Marysville’s existence the city Police Department operated on a shoe-string budget. Very few officers were full-time, and the department relied on reserve officers called into service when needed to fill gaps. Budget constraints also meant that the department did not have the cutting-edge technology that larger departments had, including technologies that allowed officers to communicate with dispatchers, and with each other while out patrolling the streets. In 1949 when the “new” City Hall (later the Ken Baxter Center) and Police Station was built in Comeford Park, the Police Department decided that the water tower right outside their office could help fill that communication gap. A red light on installed on the top of the tower, and the light was used to communicate with police officers in the absence of a central command, or walkie talkie system. The police dispatcher would turn the light on, and officers would respond to the Police Station in Comeford Park to get information.

As time went on, and communication technology become cheaper and more mainstream, the Marysville Police Department installed two-way radios in all the police cars. While this solved the problem of returning to Comeford Park to receive an assignment, many officers still patrolled the town on foot, and if responding to another call could find themselves out of their car when an important call came in. Once again, the water tower was the solution to this problem. Now when the dispatcher turned the red light atop the water tower on, officers would know to return to their patrol cars to radio back in to the Police Station. Longtime Marysville resident Art Nelson was the dispatcher for the Marysville Police Department for over twenty years, and when interviewed about the system in 1994 he recalled that they never had any problems using the water tower light to communicate with the officers on patrol. That being said, when former Marysville Police Chief Robert Dryer was asked about the subject, he recalled that every so often the light would go out, and somebody would have to climb up the tower to replace it. That was a job nobody envied.

In 1974 the city upgraded the Police Department communications system, outfitting all officers with portable two way radios. This eliminated the need for the red light on the top of the water tower. However, the light stayed on the top of the tower, and in recent years the FAA has ruled that the light must remain in place given the city’s proximity to the Arlington Airport, and Paine Field.

The “Other” Tower

Marysville soon become too big to be a one water tower town. Just a few years after the completion of the Comeford Park water tower and the water works system from Edwards Springs, it became clear to city leaders that they needed more reservoir space. Marysville had seen substantial growth along Ebey Slough, where mills and other marine based companies grew their operations, as well as businesses along State and Third. Due to this growth, the city decided to construct a larger water tower on the south end of town to serve those businesses, and the residents that lived closer to the Slough. The Comeford tower would continue to serve the north part of Marysville, which was primarily homes.

This new larger water tower was built on First Street between Delta and State, across the street from the present day Ebey Waterfront Park. However useful this tower was to businesses on the south end of town, in the 1980’s city leaders began to toy with the idea of building a mall from First north to Fourth, and from the railroad tracks east to State. This idea took off, and city leaders began the process of clearing this section of town, which included the land that the south Marysville water tower was on. In the Summer of 1987, with hundred of people coming out to watch, crews pulled down the water tower, and Marysville was once again a town with one water tower. The question would soon become, could Marysville even maintain that status?

Saving Marysville’s Space Needle

In 1986, a year before the south Marysville water tower was demolished the city constructed the Cedarcrest Reservoir, which could house millions of gallons of water, opposed to the Comeford Park water towers 50,000 gallons. It was during this time that the water tower transitioned from being a functional aid to city utilities, to a cultural landmark for Marysville and its residents. The city began to decorate the tower for various holidays, and in 1988 city crews outfitted the tower with elaborate Christmas lights, and it became the centerpiece for the Merrysville for the Holidays celebration in Comeford Park. With this new purpose, the water tower had found a new way to remain relevant in a town that had changed so much since its construction.

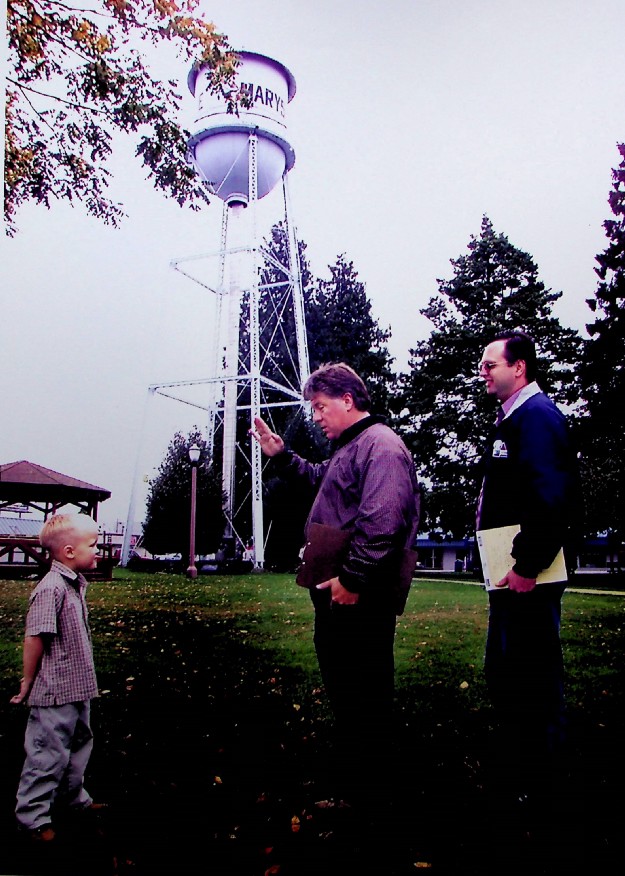

This new purpose for the tower would be short lived, as in 1999 city leaders began to have harder conversations about the water towers future. As it reached its eightieth birthday it was falling into disrepair. It desperately needed a new paint job, the roof was completely rusted, and it needed seismic upgrades to ensure it could survive an earthquake. The community was hit with the tough reality of these repairs later that year, when the city council was informed it would cost $113,000 to bring the water tower up to safe conditions. City leaders were divided on whether they should pay to fix the tower, or tear it down. Marysville Historical Society President Steve Edin was an employee for the City of Marysville at the time, and had heard the background conversations going on regarding the future of the water tower in the months leading up to this. With the images of the south Marysville water tower demolition a decade earlier fresh in their minds, Edin and the organization spring into action. In late 1999 the Marysville Historical Society began lobbying Mayor Dave Weiser, and the city council to save the water tower, in addition to this they contacted all the local media that would listen, this kicked off months of constant press attention. On one occasion society President Steve Edin went on a local Seattle news station and likened Marysville’s water tower to Seattle’s Space Needle, a comparison that stuck.

Over the next three years the Marysville Historical Society would talk to anyone who would listen about the water tower. They hosted community meetings, fundraisers, and even waved signs on the Ebey Slough Bridge to rally support for their cause. As their crusade went on, the city council was offered a $55,000 bid to demolish the water tower. Society President Edin and the city council worked out a deal, the city would pitch in the $55,000 that it would have to pay to demolish the water tower, and the historical society would pay the rest of the $113,000 for the repairs. The Marysville Historical Society was able to raise about $25,000 from the community, and the rest of the money came from the savings account the group had set up to save for the construction of their new museum. This in itself was a hotly debated issue within the historical society, a group that had been saving for a museum since 1974. In the end the membership of the organization agreed to spend the money from the museum savings account with about two thirds of the membership voting in favor of the move at their December 2001 meeting. With the money in hand, the historical society went back to the city council, but even still saving the water tower was not a done deal.

A contingency of the Marysville City Council believed that it was in the best interest of the city financially to demolish the water tower. Council member Shirley Bartholomew argued that the water tower no longer served a functional purpose, and it did not generate revenue for the city, so should be demolished. Council member Bartholomew was not the only member of this opinion, and right up to the day of the final vote the tower’s future was up in the air. On the night of the city council meeting, with two members absent, the Marysville city council voted 3–2 to move forward with repairs. The Marysville water tower had been saved by one single vote. The Historical Society, and the community had rallied together and saved the beloved community landmark, and on July 21st, 2002 work began to repair and upgrade the water tower so that it could continue to serve the community. For the time being, the water tower was saved.

The Tower Today

When the water tower was updated and presented to the community during the Merrysville for the Holidays celebration in December 2002 it was said that the repairs and new paint job would preserve the tower for another twenty years, at which time more upgrades may be needed. In December of 2019, seventeen years after this prediction was made, it appeared that history would repeat itself in Marysville. It was announced that it was no longer safe to send city crews up to hang Christmas lights for the annual tower lighting that normally took place in early December. The catwalk around the tank that crews normally walked on to hang the light had rusted so much that it was unsafe for them to perform the work. Just as had been done twenty years earlier in 1999, city leaders began to have the tough conversations about what would be the future of Marysville’s water tower.

In early 2020 the city council began the long process of deciding what to do with the tower. Initially put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the action was delayed until early 2021 when leaders received bids to repair the tower, and bids to demolish the tower. During their regularly scheduled August recess the Marysville City Council met in a special session to discuss the future of the water tower as the the need for repairs become more pressing. During this meeting it was recommended that if they wanted to preserve the tower, they would need to strip the tower down to the metal and then repaint, opposed to just doing another top coat. This option would preserve the tower for another thirty-five years, the top coat would only last another twenty. Additionally, if the city opted to strip the tower and repaint, crews would need to fully wrap the tower, as the paint used in the past contained lead. After taking the rest of the month of August to study the proposals and weigh the costs of repainting and repairing, against demolition, the city council voted unanimously to proceed with a full repaint. Work began in October of 2021, and the tower is expected to once again be presented to the community in January of 2022. For the second time, the Marysville water tower had been saved.

The Marysville water tower is one of the only landmarks in Marysville that brings with it so much history, and so much community admiration. Originally constructed after years of debate, and seen as the solution to Marysville’s pressing water crisis, its usefulness did not stop there. The water tower grew with the city, and adapted to the needs of those it provided drinking water to, serving as an aid to the Police Department in keeping Marysville safe. Even after it was drained of all water and discontinued from active use for the water works system, it found usefulness in helping the city celebrate the Christmas season, and became the centerpiece for the Merrysville for the Holidays festival in Comeford Park.

The true testament as to how the community feels about their landmark is how hard they fought to save it not once, but twice. Residents of all backgrounds, and of all age groups advocated to keep the tower when it was threated with the wrecking ball. Elderly residents wrote letters to the editor describing memories of climbing the tower in high school, and young residents drew pictures in their classrooms and made popsicle stick dioramas of the tower to show their support. If anything has come out of the last one hundred years, and the fight to save it over the last twenty, it is that the community loves it, and wants to keep it. Because of this, the Marysville water tower will continue to watch over the city for many more years to come, and remain the centerpiece our city needs.